March - April 2016

Jodi (second from the right) with Dino Martins (Mpala), Cathy Watson (ICRAF) and Wanjiru Kamau-Rutenberg (AWARD) in Nairobi, Kenya.

Dear Friends,

Happy Spring! We are currently in the midst of placing our 2016-17 fellowship class. We look forward to introducing you to our new Fellows this summer! In the meantime, we hope you enjoy reading this month’s edition of the Fellows Flyer, which includes photos taken during our annual mid-year Fellows’ Retreat in Moshi, Tanzania, as well as other photos of our alumni and Fellows meeting up across the African continent.

This month’s Flyer includes an excerpt from a Fellowship Organization Profile of Clinton Health Access Initiative, written by Lauren Theis, our 2015-16 Fellow with CHAI in Swaziland (to read the full profile, stay tuned for our annual newsletter in late May/early June!) To date, we have placed five Fellows with CHAI, including two other 2015-16 Fellows, Mariah Wood and Melissa Barber, who are based in South Africa.

We hope you enjoy this edition of the Fellows Flyer!

Warm regards from Princeton,

Jodianna Ringel

Executive Director

PiAf Connections

Please click below to check out pictures of our Fellows, Alums and other members of the PiAf family meeting up at home and around Africa.

Notes from the Field

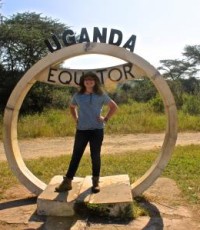

By Martha Bierut, 2015-16 Fellow with The Kasiisi Project in Uganda

Many cultures throughout Africa emphasize the use of elaborate greetings to friends, family, and even those you pass by on the street. Unique to my region in western Uganda is the added use of the “empaako” or pet name. There are about a dozen empaakos that are assigned to all children at a very young age and are eagerly designated to visitors and new residents. Each empaako means something in the local language, Rutooro, and I was pleased to discover that they fit the personalities of my coworkers and friends well. It might be an added factor of stress to have to remember everyone’s birth name and their empaako, yet it adds an instant sense of familiarity and camaraderie with everyone you encounter. These are the empaakos of some of the people close to me in Uganda (with a handy pronunciation guide):

+ Amooti (Ah-MOH-tee; royalty): the Project Director of my organization and main boss in Uganda exudes and is respected like the utmost of royalty.

+ Abooki (Ah-BOH-kee; intelligent, one born after twins): the Field Director of my organization, Amooti’s youngest sister, is very smart and strategizes for my organization’s development.

+ Akiiki (Ah-KEE-kee; brave one): the intern at my office is fiercely independent as a 20-year-old Ugandan woman and is one of my closest friends.

+ Ateenyi (Ah-TEN-yee; wise as the serpent of Muziizi River): the Conservation Education Coordinator knows everyone around our village and near the forest, bringing his knowledge and inexhaustible connections to help enrich our programs.

+ Atwooki (Ah-TWOH-kee; loyal one): the Boys Health Coordinator at my organization is very hardworking and also incredibly selfless and kind.

+ Abwooli (Ah-BWOH-lee; catlike, womanly): the Girls Health Coordinator at our office is like a mother to the rest of the staff.

+ Adyeeri (Ah-DYEH-ree; happy, laughing): the head teacher of Kasiisi Primary School wears a constant smile and loves to help out our organization.

+ Araali (Ah-RAH-lee; like lightning and thunder): when I need to get to town quickly, Araali is the one to call; he’s my favorite boda-boda (motorcycle hire) driver and is very reliable.

+ Apuuli (Ah-POO-lee; doglike, manly): the security guard for the compound where I live keeps me safe and is always telling me stories.

At the end of my first week at Kasiisi Project, my coworkers organized a big lunch for me and carried out an “empaako ceremony,” which involved a huge, traditional Ugandan meal and my participation in making millet. Ever since being given my empaako, my coworkers almost exclusively address me or refer to me in that name. Whether I’m working in the office, visiting one of our schools, or in Fort Portal town, I’m constantly experiencing the use of empaakos. It makes me feel honored and very happy to have been readily welcomed into my workplace and community at large with this tradition. As far as many of my friends and acquaintances in Uganda know, my name is Akiiki.

Notes from the Field

By India Bulkeley, 2015-16 Fellow with The BOMA Project in Kenya

“Can you tell me a time you couldn’t feed your children?”

“What is your dream for the future?”

“How has your life changed since you joined the BOMA Project?”

I’ve just traveled for 6 hours from my home in Nanyuki to Korr, a small village in Northern Kenya. I’m sitting in a small hut with a BOMA participant, two of her six children, a goat, and a translator.

Interviewing participants in my position with the BOMA Project has been by far the most rewarding and challenging aspect of my fellowship. There’s something distinctly strange about asking a person you have just met to reveal to you her life story. After 10 minutes I often know more about a stranger’s hopes, dreams, and fears than I know about some close friends. The most important skill I’ve learned – to adjust to my work as well as living in Kenya – is openness: to be open about my intentions and to not be afraid to ask the tough questions. Before I interview participants, I introduce myself, my purpose, and make sure I’m respecting the space and dignity of the women we work with.

The concept of openness goes both ways – I’ve been surprised countless times by the level of openness the participants express with me. Coming from another country, not speaking the language or sharing a similar culture to these women, I was expecting there to be a barrier between us. I was surprised to be welcomed into the homes of countless women and have my questions answered without hesitation. It’s easy to assume that certain topics that are taboo in my culture, such as hardship and struggles, are not so unmentionable here. Women living on less than $1 a day are used to talking about the difficulties of day-to-day life.

As my fellowship year comes to a close, I look forward to continuing to have these open conversations – both personally and professionally.

Notes from the Field

By Kendall Carpenter, 2015-16 Fellow with Baylor International Pediatric AIDS Initiative in Botswana

“Why don’t they just take their medication?”

I’ll admit that this thought went through my mind numerous times after I got my fellowship offer but before I’d arrived in Botswana. It was while investigating challenge patient programs that this pesky question kept intruding. I’d try my hardest to swat it away as soon as I heard the first buzzes of judgment.

“But this could mean life or death… if the HIV becomes resistant…”

I pushed the menace back again.

“There must just be a lack of understanding on what the drugs actually do. “

I entered Botswana with this mindset. Two months into my program, however, this neat little theory of mine was shattered. When asked to analyze data from challenge patient surveys I found that not only did these patients understand ARVs, they arguably understood them better than I did. In answering what ARVs do and why it is important to take your medication, almost every survey included the words CD4 cells, cellular machinery, AND resistance. They understood that by not taking their medication, they were putting their lives at risk, yet they continued doing it.

The work that I did on this report would prove invaluable when I was asked to coordinate an adherence camp. The camp’s aim was simple yet unbelievably ambitious: to get the clinic’s most long-standing challenge patients, those who have been struggling with adherence for 2 plus years, to improve their adherence and ultimately their health.

I was tasked with writing the curriculum alongside Baylor’s social worker and psychologist. Throughout this camp I realized just how many different reasons the patients had for not taking their medication. None of them, however, revolved around a lack of information. It was a lack of status acceptance, fear of discrimination, minimal familial support, size and smell of the pill, etc. In that moment I recognized a concept that I had been dancing around for years but could never pinpoint: there is a human aspect to medicine that goes beyond diagnostic tests, surgeries, and medications.

What I have come to realize is you could have the best medical treatment in the world: speedy diagnosis, top-notch surgeons, cutting-edge medications, but if you don’t feel supported, whether that be by your family, friends, physician, or community, you won’t have positive clinical outcomes. These challenge patient campers weren’t getting that support in some aspect of their life. Since camp, I have heard from many patients that the camp activities and friendships they created have completely altered the way that they think about adherence. It wasn’t that they needed more information about their medications but rather it needed to be talked about it a different way, one coming from a place of understanding, empathy, and emotional validation. Over the past few months the question has transformed in my mind from:

“Why don’t they just take their medication?”

To:

“How can we support them in taking their medication?”

Notes from the Field

By Jasmin Church, 2015-16 Fellow with eleQtra (InfraCo) in Uganda

Jasmin (bottom left corner) pictured in Uganda’s New Vision newspaper cheering at the Uganda vs. Togo soccer game at the Mandela National Stadium in Namboole, Kampala, Uganda.

What do you get when you take a New Jersey raised, former DC banker who is used to routine and control (sorry, oldest of five) and place her on a completely new continent for one year? An uncomfortable, complaining, mess! It turns out that adapting to West Virginia for a summer is quite different from adapting to Uganda for a year. Go figure. But once I returned from visiting home for Christmas – it happened. Uganda took me in its arms and became my home. The ups, the downs and everything in between…

Up: “Jasmin, you are not abroad, you are in Africa”

On a Friday night in Kampala I was chatting with a local about some of the Ugandan traditions, processes and systems I felt were keeping me from adjusting. I told him “Hey, maybe it’s because this is my first time living abroad” and he responded, “Jasmin, you are not abroad, you are in Africa.” And just like that, I began to think of Uganda as home and adjusting became much easier.

In between: “Jasmin, you’re in a tabloid”

My second weekend in Uganda, I went to a music festival at the National Museum. I met tons of people from all over the world. On Monday morning, I arrived at work and my coworker shouted, “Jasmin, you’re in a tabloid, you’re famous.” A picture of me sitting with a local Ugandan man I met at the festival was in the local “tabloid” newspaper called Red Pepper with the caption “a lovely couple enjoying the festival.” Awkward.

Up: “Jasmin, are you trying to corrupt us with your Western views”

Lunch hour at work in Kampala is completely different from lunch hour at work in NYC – it’s family style around a large table. My coworkers (who have become family) and I always have the best conversations with no inhibitions. From politics to relationships to homophobia to reality TV, we discuss it all. And things can get quite frank when I start preaching my feminist beliefs and one of the guys jokingly asks “Jasmin, are you trying to corrupt us with your Western views.” Such genuine relationships and bonds are the most rewarding part of my experience.

Down: “Vegetables? Jasmin, we’re not goats”

Staple Ugandan dishes include matooke, posho, rice and potatoes – carb nation! All served together and accompanied by a protein and a tablespoon of spinach. Of course there are tons of fresh veggies and fruit in the Pearl of Africa but eating them with meals is not the usual. And each time I ask why, a local explains “Vegetables? Jasmin, we’re not goats.”

Up: “Jasmin, you’re a celeb!’

One Sunday in November, I attended my first professional soccer game (Uganda vs. Togo) – the energy and experience were beyond amazing. And on another Monday morning, a coworker greeted me with a copy of New Vision (a local newspaper) and said “Jasmin, you’re a celeb.” I was in the newspaper AGAIN but this time repping Uganda!

Notes from the Field

By Michael Elhardt, 2015-16 Fellow with eleQtra (InfraCo) in Ghana

Michael (left) with fellow 2015-16 Fellows Monique St. Jarre (center) and Akinyi Ochieng (right) at the Chale Wote Street Art Festival in Accra, Ghana.

“Mille deux cent?” she asked in disbelief, “Mille deux cent?!” Justine, a jovial woman with long braided hair, and my host whom I had met only three minutes earlier, burst into laughter upon hearing just how badly I had been ripped off by my first motorcycle taxi in Togo. And she was right: the ride from the Ghanaian border to her home near the sandy beaches of southeastern Lomé should have cost less than half of what I had paid.

Now, to be fair, it was my first experience in a Francophone country and my French was rudimentary at best. Negotiating a fair price had taken a backseat to simply finding my host before the sun went down. So how had I even gotten myself into this situation? Well, my fellowship is based in Ghana, but for the holidays I had decided to challenge myself with a solo trip through the neighboring countries of Togo and Benin. My priority was to travel cheaply and meet locals, so I tried my luck with Couchsurfing (an online community where people open their homes to travelers free of charge). It was a choice that allowed me to see Lomé in a way that wouldn’t have been possible alone or with other expatriates.

After entering her home, Justine promptly introduced me to her friends Kiki and Aya. Both men were passionate reggae musicians who also shared a talent for painting. Together they all helped run a small non-profit geared towards providing food and artistic activities for Togolese orphans. For the next two days before Christmas Eve we gathered art supplies and planned the lunch that would be prepared at a local children’s home. Through a combination of their broken English and my possibly even more broken French we decided that my job would be to help Kiki with the art activities. This was fine with me as I didn’t want my cooking to ruin Christmas for a bunch of small kids.

December 24th finally arrived, and it could hardly have been a more amazing day. Aya manned his drum and led groups of kids in Christmas carols with the odd reggae classic thrown in here and there. Several children and I compared our crayon-drawn creations while Kiki handed out paint brushes and encouraged everyone to join in on a large mural. The only break in the artistic frenzy came when Justine presented several large pots of boiled fish and rice.

That night I welcomed Christmas to the soulful rhythms of Kiki’s band at a local bar. The choruses of “One Love” and “Jammin’” echoed in my head while I processed the day and thought about the remainder of my journey. I had been so concerned after that first encounter with the motorcycle taxi that the language barrier would keep me from enjoying the trip. It turned out that my French had already begun improving and, whether through art or music, there were plenty of other ways to communicate too.

Notes from the Field

By Melissa Gibson, 2015-16 Fellow with UN World Food Programme in South Africa

Melissa (left) hiking in Swaziland with fellow Fellows Mariah Wood (center) and Lauren Theis (right).

I am a creature of habit. I crave routines, structure, and organization. Most mornings start the same: 6:20AM alarm goes off; 6:22AM roll over and pretend I didn’t just hear the alarm going off; 6:24 surrender to the day; make bed; make coffee; get dressed; out the door by 7:15. Back in the States, what happened next – what happened once I stepped foot outside – was more or less predictable. (Class 9AM-11AM, work 11:30AM-1PM, etc.) Here in Johannesburg, there is no telling what the morning will have in store. Taxi buses swerve in and out of lanes, sometimes causing me to spill precious amounts of coffee and/or utter some choice words. Traffic lights, or robots as they’re often called, may or may not be working – meaning it may take me 30 minutes to get to work, or it may take me an hour and 30 minutes. Once I get to the offices of the UN World Food Programme, things may be calm – a couple reports to write/edit, some emails to read through – or things may be chaotic, with people running around like headless chickens because the President of Zimbabwe has just declared a state of drought emergency and is asking for USD 1.5 billion in assistance.

As someone who used to live each day according to what was written down in her calendar, learning to just ~go with the flow~ and ~expect the unexpected~ has been challenging. In fact, throughout my first couple of months here in Jo’burg, I felt as if I was suffering from a severe case of whiplash. On May 2, 2015 I graduated from University and left the small college town that I’d grown so accustomed to it felt like I recognized each crack in the sidewalk. On July 19, 2015 I celebrated my 22nd birthday. Six days later, with a one-way ticket in hand, I left for my post with WFP. Two days after landing in a mist-covered Jo’burg, I found myself wandering – albeit in a jet lag-induced daze – the halls of my new office. I tried to remember the last time I felt this lost. Project acronyms were thrown at me right and left. The food the canteen served was unfamiliar. I struggled to remember the names of my co-workers. I was, however, lucky to overlap with not one, but two, of this post’s previous Fellows. I wrote in my journal about how they both seemed so settled in Jo’burg and how I doubted I would ever feel that way.

Well, as I approach the seventh month of my fellowship, I can confidently say I feel that way. I zip around the city in my beat-up little Honda (I have affectionately named her Kelly/K.C., after Queen Ms. Kelly Clarkson). I’ve discovered new tastes: boerewors and malva pudding are both very good. Biltong and ostrich meat…not so much. I feel so integrated into my office I’m treated more as a staff member and not a ‘Fellow’ or ‘intern.’ I may not recognize the cracks in the sidewalks anymore, and my mornings may forever be unpredictable, but as Queen Kelly once said: “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.”

Notes from the Field

By Margaret Gould, 2015-16 Fellow with Maru-a-Pula in Botswana

Meg (far back row, on the right) with her Form 1 students after winning a soccer match against a visiting team from South Africa.

“Ma’am, it’s beautiful!” were the last words I expected to hear from the twenty-nine other people in the room. The people were my fifteen-year-old students… in response to learning simultaneous equations.

At the start of teaching math at Maru-a-Pula Secondary School in Gaborone, Botswana, I felt small success: students learned, but without the visceral reactions of inspiration I’d imagined. Yet something clicked that day. As they exclaimed with every newfound answer to these previously frustrating riddles, I realized that finding equations “beautiful” was a result of authentic discovery.

Often I consider how lucky I am to contribute to these moments of discovery. Teaching students at MaP means seeing exhilarating growth: students become enthralled by math, writing, and debating, or find their niches in performance or athletics. And similarly to my students, I’ve had many transformative discoveries over the past eight months in Botswana.

First, I’ve discovered that learning and teaching are not aligned with age. When traveling with students to a refugee camp, I learned the power of connection from students opening their hearts to instant friendship, and minds to facing the challenging, yet realistic issues within the community. Daily, my students expose new ways of viewing (and solving) problems. Moreover, I’ve found that unsolicited kindness and indiscriminate inclusion, regardless of nationality or age, are inextricably woven into the fabric of life in Botswana. Everyone greets with a grand “Dumela” (hello), and it is natural to play hours of pick-up frisbee with strangers who become friends, offer rides without being asked, or host impromptu braais (BBQs) to enjoy Botswana’s warm, long nights.

Natural resources have also taken on new importance. With the drought enveloping Southern Africa, our adopted school mantra, “If it’s yellow let it mellow…” (you know the rest) could be applied countrywide, and load-shedding the electric grid is routine. However, I’ve discovered the alternative to showers is wearing braids… and that often lessons are more creative sans electronics. And certainly, without fail, every drop of rain – or “Pulaaa!” – universally breaks out the smiles.

As familiar as Botswana can feel, I have yet to discover all the contrasts of life here. When is “lunch break” an hour, or a relative term? When does simple, teenage behavior drift into the consequences of serious and complex emotional, familial, or financial situations When do I cross the line from “teacher” to mentor, or coach, or even friend? Is the experiential learning we often do in afternoons – dialogues on global awareness or personal identity, or traveling into the community to work with service organizations – better than the morning’s academic schedule? Most importantly: KFC or Chicken Licken? The questions – ranging from inquiries into the school community, broader Gaborone, or even the quirks of Botswana itself – not only expand, but their elusive answers constantly change and transform.

It seems that I’ve come to a similar conclusion as my students did: even with the daily riddles, there is a simultaneous joy and challenge of each moment here, and I have four months left to keep discovering.

Notes from the Field

By Caleigh Hernandez, 2015-16 Fellow with International Rescue Committee in Kenya

Caleigh (center) with two WEKEZA livelihoods beneficiaries. They were trained in how to properly grow various crops in order to increase their incomes and stop relying on their children as a source of income.

I came across Evod while in the field conducting interviews on some of our most successful beneficiaries. We drove an hour and a half into the “bush” to meet with this young boy. We were told he was the best in the class now that he was attending school regularly with assistance from WEKEZA. I was to interview him as part of a larger project to highlight some of WEKEZA’s success stories. WEKEZA is a development project supported by the IRC that works to reduce the prevalence of child labor. We provide students with schools fees and school uniforms to reduce barriers to school attendance and work with their families to increase incomes and reduce reliance on children for income.

Evod was shy the entire interview; I didn’t think much of it. When I did finally make eye contact with him, I noticed that his eyes involuntarily shook. Evod disclosed he has an eye condition making it difficult to focus on what he sees. He has to stand close to the chalkboard in order to see anything clearly and even then it is still challenging. He sought a diagnosis from a free mobile clinic that came to his village, but they did not have enough time to see him before leaving.

I spoke with the WEKEZA team and asked if there was any way we could help Evod. They sympathized but argued that it was outside of their mandate. His eye condition did not make him more susceptible to being exploited for child labor. I understood their constraints, but had access to resources and a responsibility to do something. So I started researching (don’t WebMD anything, it’ll scare you) and reaching out to friends and family. I sought advice from ophthalmologists back home and found the only ophthalmologist in the region, Dr. Kibadi, to bring Evod in for a consultation.

After receiving permission from the local government to take Evod and his uncle to the doctor, we went to see Dr. Kibadi. Long story short, Evod was diagnosed with a congenital condition. While there was nothing that could be done to solve his condition, we could lessen his symptoms through glasses and diet. While it’s by no means a complete or sustainable solution, at least Evod and his family have information on his condition and are better equipped to manage his symptoms. It was a lack of resources that prevented them from accessing this information earlier.

The system in Tanzania is so weak it fails anyone with limited resources regardless of their potential, but the same can be said for aid projects. This isn’t a new revelation, but the aid sector is more donor- than needs-driven. Despite the comprehensive WEKEZA intervention in this rural village, there are still huge needs that are not being met. While Evod is just a small example, it goes to show that new mindsets need to be adopted before we start to have the largest impact possible in development projects.

Notes from the Field

By Tyler McBrien, 2015-16 Fellow with Equal Education in South Africa

When I arrived at Equal Education, I quickly realized that there were two languages I would need to learn to successfully support the organization. The first is isiXhosa, the language overwhelmingly spoken in the area of the Eastern Cape in which we work and organize. The second language sounded slightly more familiar. It included English words I recognized, but somehow they felt more meaningful – more powerful. I was hearing the language of activists.

Language matters. Words matter. As I attended community meetings, in-school rallies, and other gatherings of student activists, I began to understand that certain words empower you just by speaking them. This especially rings true in a country with a legacy of some of history’s most famous activists and revolutionaries. Certain words can associate your message with the likes of Mandela, Biko, and Tambo.

Activists must pay especially close attention to language as they craft their message to potential allies or to those with the power to make positive change. While writing newspaper articles, drafting campaign leaflets, and even tweeting, I have labored over words and meaning.

As one of the founders of Equal Education said, EE “teaches people how to become citizens and how to struggle as they had in the past, but to do so within a constitutional framework, where the aim was no longer to overthrow the state, but to implement the bill of rights.” Language serves as one of the tools to get there.

Below is a far from exhaustive dictionary of the language of activists:

Revolutionary greetings!: There really is no better way to start a day of activism than with a hearty “Revolutionary greetings!” from one of your colleagues. But even more, morning greetings build camaraderie and develop relationships. I heard my first “revolutionary greetings” at a community meeting of several schools I had helped to organize.

Comrade: A comrade is more than a colleague, even more than a friend. Equal Education comrades share a common mission. While working in the Eastern Cape office, I helped design a survey to audit school infrastructure in the province and reach out to principals and let them know they have comrades at EE.

A luta continua: Or, “the struggle continues.” This is often a rallying cry spoken alongside “every generation has its struggle.” This is also the tagline of Equal Education Radio, an education-focused podcast and community radio show that I produce with EE colleagues.

Movement: Equal Education bills itself as something larger than a non-profit organization – a social movement. The movement derives its campaigns, its direction, and its power from the EE membership, which consists mostly of high school students. In this model, EE directly engages and follows those affected by the work.

Notes from the Field

Fellowship Organization Profile: Clinton Health Access Initiative (written by Lauren Theis, 2015-16 Fellow with Clinton Health Access Initiative in Swaziland)

To read the unabridged version of this profile, as well as other articles written by our Fellows about their work, please stay tuned for our Annual Newsletter in late May/early June!

While Clinton is a household name in America’s heated political discussions, many households across the globe use the Clinton name while discussing transformative health improvement strategies. The Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) was founded by President William J. Clinton in 2002 with a single goal: “help save the lives of millions of people living with HIV/AIDS in the developing world by dramatically scaling up antiretroviral treatment.”

CHAI is now supporting 33 governments and 70 countries in building capacity to deliver high-quality care and treatment programs, particularly for the high disease burden areas of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. CHAI’s country teams conduct work in areas ranging from optimizing human resources for health to altering commodity markets to decrease care and treatment costs and accelerate access to life-saving health services.

As the 2015-16 Princeton in Africa Fellow at CHAI Swaziland, I am able to approach global health through the lens of the Sustainable Health Financing team. The goal of CHAI’s health financing work is to help “remove financing as a barrier to achieving universal health coverage” through improved understanding of resource needs, management of existing resources, and security of long-term health funding. During my fellowship, this approach has allowed me to work hand-in-hand with government actors across the health system to improve financial management tools and processes for efficiency and effectiveness of spending.

My experience as a PiAf Fellow has challenged my understanding of sustainability, a key facet of CHAI’s large-scale, high-impact work; CHAI does not intend to be a permanent fixture in a given health system, and thus our work must be simultaneously government-led, evidence-based, and impactful. My experience as the CHAI Swaziland PiAf Fellow has given me the unique opportunity to straddle government and NGO approaches to support cohesive and sustainable health system transformation, and I am excited to carry the CHAI values and perspective throughout my global health career.