May - June 2015

Dear Friends,

It’s official: we’ve placed our newest fellowship class! We will have 51 Fellows working with 31 organizations in 15 countries for the 2015-16 fellowship year. We were thrilled to welcome our Fellows at their orientation weekend in Princeton, NJ in early June. We also enjoyed connecting with PiAf Fellows, board members, alumni, and friends during Princeton’s annual Reunions weekend in late May. You can check out pictures of PiAf’s Reunions events and Fellows’ Orientation here on our Facebook page.

In this Fellows Flyer, our Fellows describe teaching history & geography and building community in Botswana, working to improve the livelihoods of women shea collectors across Africa, and more. As always, we hope you enjoy this edition of the Fellows Flyer!

Warm regards,

Katie Henneman

Executive Director

PiAf Connections

Please click below to check out pictures of our Fellows, Alums and other members of the PiAf family meeting up at home and around Africa.

Notes from the Field

By Hannah Brown, 2014-15 Fellow with International Rescue Committee in Tanzania

Hannah (left) and fellow IRC Tanzania Fellow Akua Agyen coming back from the field overlooking Kasulu.

Being located at a fairly isolated post means a lot of time in the car. From Kasulu to Nyarugusu Refugee Camp, one hour each way. From Kasulu to Kigoma (the regional capital), two hours each way. From Dar es Salaam (the national capital) to the IRC office in Tanga, six hours each way.

Initially, I did not think I was going to particularly enjoy these journeys. If you get stuck behind another car in the dry season, the dust is so great you cannot make out the lights of the vehicle ahead, while you simultaneously roll up your window quickly to prevent a severe inhalation of vombe (dust in Swahili). If you attempt to catch a nap, it may last a minute or two if the unpaved roads’ divots and bumps don’t disturb you. And if it’s the rainy season, you may find yourself holding your breath and hanging on tight as the vehicle slips and slides through the mass amounts of tope (mud in Swahili).

However, when I reflect on it, I realize that I actually have come to really enjoy these drives. Here are some of the myriad reasons why, in no particular order:

+ The breathtaking scenery—I live in a gorgeous region, there is no doubt about that. During rainy season everything is so lush and, contrasted with the deep red earth, bright green foliage pops out everywhere. As you wind your way to Kasulu, up and down hills as if they were painted on a forged backdrop, you may roll your window down to catch a cool breeze and breathe in the unpolluted fresh air of Kigoma region.

+ Eating nanas (pineapple in Swahili)—The nanas on the way from Dar es Salaam to Tanga City are out of this world. About three hours into the trip, stands start popping up along the road. You see young men stacking and hanging hundreds of nanas, waiting anxiously for the next customer. As you pull over, someone runs over, asking you how many while already cutting and slicing one in their hand. They pass over a bag full of fresh and juicy nanas that melt in your mouth as you continue on your journey.

+ Conversations with drivers—Anything is a potential discussion topic, and I have learned more on my car rides than I could have imagined. Conversations vary depending on the driver’s level of English. To break the silence one day I pointed to the windshield to indicate a crack and ask what happened. The driver responded with, “Yes, rain.” However, I’ve also had an in-depth chat about racial inequality in the U.S. We discussed the deaths of unarmed black men including Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Walter Scott, and Freddie Gray, to name a few, and hearing a Tanzanian perspective was quite enlightening.

+ Celine Dion—Need I say more? Celine is a personal favorite of many IRC drivers, and each driver is always ready to crank it up and let the sing-a-long begin. I think Celine Dion really could bring the whole world together.

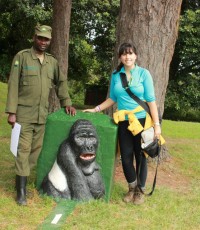

Nava (right) standing with her mountain gorilla trekking guide, Johns, just after finishing a trek in Bwindi Impenetrable Forest in southwestern Uganda.

The Unexpected Adventure of Learning (and Unpacking) a New English in Uganda

Development work comes with its own lexicon. Acronyms, buzzwords, catchphrases – these are the stuff such work is made of. “Our HCT outreaches in hard-to-reach areas, coupled with the VMMC and PMTCT efforts that have been implemented in partnership with the DHO, have really helped stem the flow of HIV transmission in Kabale district.”

Working on reporting and communications for Plan, I spend much of my day immersed in a Ugandan dialect of this language. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed absorbing the cadence of the English that is spoken here and learning the rhythms of the phrases (instead of “for real!” you say “by the way!”; when anything bad happens from a toe stub to a massacre, you say “sorry!”). Seeing how Ugandan English intersects with NGO-ese has been an unexpectedly fascinating adventure, as has trying to parse out what requires translation for our donors. This language exercise has persuaded me of the essential but complex role of speech in the way development is enacted on a daily basis.

Imagine arriving in a village and a community member, who speaks fluent Lusoga but fairly rudimentary English, starts talking about the need to “sensitize” and “mobilize” the community.

Ugandan NGO-ese is fascinating in the way it flows down to communities with whom organizations work. While this may not detract from the work that Plan and its peers do, it brings up questions about power dynamics, the thick presence of NGOs in communities’ daily lives, and the complicated ways in which development organizations and their funders act as sources of knowledge and connection for beneficiaries. While I plan to read more on these issues, for now, I simply offer a few of the words I see most, along with their local translations. Many are used beyond the NGO world, though I can’t answer the obvious “chicken and egg” question (which came first, the word usage or the NGO?)

Awareness-raising: Making people aware of a social issue that needs to be tackled or a right to which they should have access. Is used as an adjective as well as a noun, i.e. “they are planning an awareness-raising.” See also: sensitize.

Facilitate: To help run an activity; usually this refers to paying for the activity as well. Sometimes it purely refers to paying for an activity.

IEC materials: Information, Education and Communication materials; pens, notebooks, T-shirts, hats… or anything else on which you can put the name of an NGO or implementing partner.

MDD: Music, Dance and Drama; artistic methods that can be used to convey messages about HIV, education, early marriage, etc.

Mobilize: To get people to do/be involved in an NGO-recommended/run activity.

Outreaches: Any activities that involve going into villages/areas that are harder to reach and performing an NGO activity. Often health-related.

Sensitize: To let people know about a certain issue that an NGO deems important. It is usually aimed at helping people change an aspect of their current behavior or pursue some kind of intervention (be it health, education, etc.)

Notes from the Field

By Rebecca Liron, 2014-15 Fellow with International Rescue Committee in Kenya

Living in Nairobi for the last nine months working for the International Rescue Committee in Kenya, I think it best for me to sum up my experiences in what I’ll refer to as “Kenya-isms”:

Me, I love Nairobi – As my new favorite T-shirt expresses, I’ve learned to love Nairobi. Once you get past the traffic and the other qualms of living in a crowded, expensive city, Nairobi unveils its heart in the amazing people, from all over Kenya and around the world, whom I’ve been lucky enough to meet. It may not have been love at first sight, but Nairobi will forever hold a special place in my heart.

By the way – During my field visit to Kakuma Refugee Camp, I learned from my co-workers that “by the way” is applicable in any part of a sentence, in any context. You really have to hear it in use to understand. Aside from this revelation, my time in Kakuma has been one of my most memorable and valuable experiences during my fellowship thus far. I was able to meet IRC’s Kakuma staff, visit IRC’s hospitals, health clinics, and women’s centers in the camp, and interact with inspiring refugees from Congo, South Sudan, Somalia, and Ethiopia – 4 of the now 18 nationalities represented in the camp.

Sawa, sawa – Meaning “right” or “okay” in Kiswahili. You’ll often hear “sawa” at the end of most sentences, and I now find myself confirming with a “sawa,” even when Skyping with friends from home. Something so simple as a call and response, “Sawa? Sawa,” has become ingrained in my daily life, and something that I won’t be able to help continuing once I leave Kenya.

Hakuna Matata – Lion King reference? Yes. But after a recent visit to the Maasai Mara for a safari with my family, I have confirmed that “hakuna matata” is not the only accurate depiction of Kenya that comes from The Lion King. For the record, the savannah and animals in the movie are extremely accurate, down to the lion roars and the Pumbas. “Hakuna matata,” which really does mean “no worries” in Kiswahili, has been said to me in the context of appeasing tourists, even from airport employees reassuring me that “this is Africa,” and things move at a slower pace (even when I did, indeed, miss my flight). However, I think “hakuna matata” is most applicable in what living in Kenya has taught me. I’ve learned to slow down, go with the flow, and appreciate what I have.

Karibu – “Karibu” is Kiswahili for “welcome,” and “karibuni” is the plural version. “Karibu Kenya” was one of the first familiar phrases I heard, getting picked up from the airport and entering another PiAf Fellow’s apartment for my welcome pizza party. My co-Fellow and roommate Ellie says “Karibuni,” most often to one person instead of multiple, and saying it just to say it. This “Kenya-ism” will always remind me of how welcoming Kenya has consistently been to me throughout my fellowship, and I’ll forever hear “Karibuni” in Ellie’s voice.

Notes from the Field

By Gabriel Nahmias, 2014-15 Fellow with Equal Education in South Africa

How to be an Outside Agitator in 5 Easy Steps

The American South has been, from Birmingham to Ferguson, a popular destination for “outside agitators.” As a citizen of the South, I’ve benefited particularly from these liberal interventionists, and so with pleasure I bear the title of “outside agitator” today. I work with Equal Education, a South African activist movement that is training and organizing working-class youth to fight for a better education. Below are some lessons learned as a foreigner fighting for equality in South Africa:

Step 1: This is Not Your Fight

To some degree this isn’t true. The global economy ties your fate and history to that of all people. A major company that has been exploiting South Africa’s mines for a century is “Anglo-American,” after all. However, I never lived through Apartheid. I don’t live in Khayelitsha. I don’t go to a South African school and never did. I don’t have any skin in the game. If things go south, I get to leave. I need to respect that fact and how it influences my place. For the outside agitator, this means that at times you have to step back, shut up, and listen.

Step 2: Be Aware of Your Ignorance

You may be worldly and well-educated, with valuable skills and impassioned beliefs, but you don’t know the context. It is humbling that despite a master’s degree in political science, I am struggling to understand the South African government – not to mention public transportation and education curriculum. Until you have lived a system day-to-day, you can’t have a true grasp of it. Always be ready to defer to the superior knowledge of the community.

Step 3: Be a Tool

What you have to give is your skills. If you have no skills, it is your hands. In my time with EE I’ve made flyers, analysed surveys, written articles, come up with slogans, prepared thousands of hot dogs, and marched many miles. Every movement requires foot soldiers.

Step 4: Be an Educator

Share what you know and think and believe, even if this challenges perspectives. This may seem contrary to steps 1-3, which emphasized being humble. But, you have a responsibility to transfer what skills you have to local activists. And, you have a right and duty to fight for your beliefs, even within someone else’s movement, as long as you do so modestly. However, educating is a privilege, not a right. You must earn it by proving your abilities and trustworthiness.

Step 5: Be Up for Anything

Oddly, the initial way I built respect was that when EE members started singing and dancing, as they often do, I sang and I danced. Sure, I couldn’t understand what I was singing and I looked like a fool. But my willingness to look the fool to be a part of the community was respected. If you’re going to travel halfway around the world to fight for something, you might as well stand up and sing about it too.

Notes from the Field

By Grace Perkins, 2014-15 Fellow with Global Shea Alliance in Ghana

Dear Grace of August 2014,

Hi! It’s me, your future self. I was thinking about you the other day and how nervous and excited you were to start your fellowship at the Global Shea Alliance in Ghana. Think of all the lessons you’ve learned since then! Man, if I had 50 pesewas for every Homer Simpson “D’oh!” moment you (uhh, I mean, I) have had here…

To my naïve yet eager former self, here are 10 lessons you’ll learn in Accra:

Ditch that fufu stuff: It’s all about the banku, baby. I know fermented maize and cassava dough doesn’t exactly sound appetizing, but trust me. It’s by far the best Ghanaian starch.

Get up early (…or earlier): You live on the equator now, so the sun has already beat you to it. But get up, go for a run. It’s quieter and cooler at this time of day.

Work your behind off: Be creative. Under promise and over deliver. Launch the African Women’s Fund and secure sponsorships from the industry leaders in shea. You’re working to improve the livelihoods of 16 million women shea collectors across Africa. You can do it.

Join that group: Wednesdays, 7:30pm. Scottish Dancing. Saturdays, once a month. Hiking.

Seek out new friends: Befriend Barbara. She’s the lady who sells jewelry on Mission Street. Not only will she become your new auntie, her laugh will brighten even the worst of days. And don’t worry if she only calls you “Becky”…because she will.

Read those articles: Take a break from work and read about the shea industry. You’re the communications manager. Do your research on how shea butter is used in your favorite food and cosmetics products.

Have that beer: I know you’re tired after work. But the sooner you get to know these fabulous, crazy people around you, the faster you’ll feel at home.

Ask for help: Six months in, ask for an evaluation. You’ll be expecting praise because you’re used to it. Don’t take it too hard when your boss tells you that you need to take more initiative. Thank him for his honesty and start thinking big.

Don’t fight the power: The electricity, that is. The sooner you learn to laugh about Accra’s erratic power supply, the happier you’ll be.

Call your friends: I know you’re on an adventure, but their love and support got you here. And prepare to get all choked up when you hear their voices from across the Atlantic.

When I finally get around to building that time machine that we’ve dreamed of since we were seven, I’ll travel back and hand this list to you. Then it will be smooth sailing from day one.

On second thought… maybe you (err, I) were supposed to learn these things on our own. Maybe the awkwardness, uncertainty, and overcoming the fear of failure were exactly what we needed. This journey has taken us to some unexpected places, but I wouldn’t trade my friends, experiences, and lessons for the world.

Love always,

Grace

Notes from the Field

By Lauren Richardson, 2014-15 Fellow with Maru-a-Pula in Botswana

Flying into Botswana in June when the winter dry season was gaining momentum, my first thoughts on the dusty country thousands of feet below my plane was that it looked sparse, dull, and relentlessly brown. The drive from the airport to Maru-a-Pula, the school where I would be teaching history and geography for the next year, was quiet. Gaborone’s streets were devoid of the humming friction derived from dense human contact that I remembered from my time in Tanzania and Kenya a year prior. Upon first glance, Botswana, quite frankly, seemed boring.

Inside the gates of Maru-a-Pula my perception of Botswana has morphed and changed over the course of my fellowship year. From the first greetings of Dumela and Yebo I exchanged with the gate guards, MaP has met me with open arms. Pula is the Setswana word for “rain,” “blessings,” or “opportunity.” While rain is definitely in short supply at this educational oasis on the edge of the Kalahari Desert, I have found great fortune while teaching at MaP. MaP exudes a feeling of inclusivity, tolerance, and creativity.

Pula of the sort that enriches the human spirit can be found as I am racing players on the soccer field, digging in the organic garden under Botswana’s bright blue skies, hanging out on the couches of the girls’ boarding house, and in the hearts and minds of the young people I work with.

The power of cultivating sincere human relationships is made clear to me every day while navigating my place at MaP. While I always try to hold my students to a standard of high individual ambition, at MaP I have learned the value of going together. I have been impressed and humbled by the huge strength and character found in the small packages that are my students. From the warmth of my neighbors and coworkers, I have come to understand that a home is not found, but is built. At MaP, even on the busiest of workdays there is time to laugh, dance and acknowledge the tiny, beautiful things that surround me. In Botswana, there is life, energy, and possibility teeming under red dust and cracked earth.

Working at Maru-a-Pula has challenged my understanding of and appreciation for community. The relationships I have built and the many miracles of human kindness I have seen during my fellowship year in Botswana are clear evidence that cohesive social capital is central to inclusive development. Working and living on the MaP campus has shown me the value of genuine probity, empathy, and care in my daily life and work. MaP has given me a rare space where the loneliness that many young people face can be cured and building community has a gratifying moral purpose.